So There May Be One Less Grieving Family

Jeanne Bishop

I am a family member of three murder victims.

On Palm Sunday, 1990, my 25-year-old sister Nancy Bishop Langert; her husband, Richard, 29; and their unborn baby were found shot to death in their home. The baby Nancy was carrying would have been their first child.

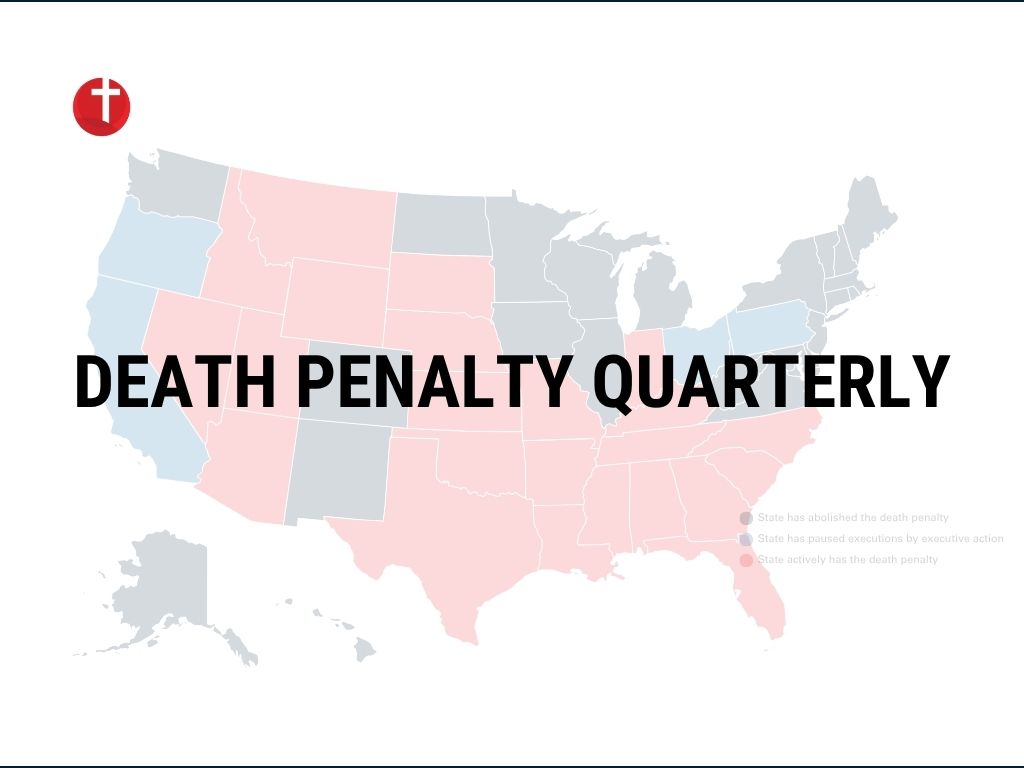

Their killer was arrested six months later after an intense manhunt. He turned out to be a 16-year-old boy who lived a few blocks away from Nancy and Richard. He went to trial at a time that other U.S. states had a death penalty for people who were juveniles at the time of their crimes. Illinois did not. (The U.S. Supreme Court has since struck down the death penalty for juveniles nationwide)

The young man was convicted and sentenced to the mandatory punishment in Illinois for his crime: life in prison without the possibility of parole. The shocking murder had drawn press attention, so after the sentence was handed down, reporters were outside the courtroom to get my family’s reaction to the life sentence. “Are you disappointed he couldn’t get the death penalty?” one of them asked me. I said, No. that I was relieved.

I don’t believe in the death penalty. Killing Nancy’s killer wouldn’t bring her back; it wouldn’t honor her memory. It would only dig another grave and shed more blood and create another grieving family.

My public stance as a murder victim’s family member who opposed the death penalty led to a wonderful discovery: there were many of us out there, people who have lost dear ones to homicide but who support an end to executions. Bill Pelke, whose grandmother, a Sunday school teacher, was stabbed to death by a group of teenage girls. Marietta Jaeger, whose young daughter Susie was abducted and killed by a pedophile. Bud Welch, whose only daughter Julie, 23, died in the Oklahoma City bombing, still the worst single act of domestic terrorism in the nation’s history. Bud and I have gone around the nation and parts of the world, including Japan and Mongolia, speaking out against executions.

I wrote a book, Grace From the Rubble: Two Fathers’ Road to Reconciliation After the Oklahoma City Bombing, to tell the story of Bud Welch and Bill McVeigh, the father of Timothy McVeigh, who set off the bomb that killed Bud’s daughter.

The two men, both cradle Catholics who still practice their Catholic faith today, found common ground in their grief. When the two men met, Timothy McVeigh was under a sentence of death for the bombing, awaiting his execution date. At the time, Bud was the father of a child who had been killed and Bill was the father of a child about to be killed. They were introduced to each other by a Catholic nun, Sister Rosalind Rosolowski, affectionately known as “Sister Roz.” The day I met her to interview her for my book, she was visiting a dying prisoner in the hospital. She walks the walk.

Jesus said that when you visit the prisoner, you’re visiting Christ himself (Matthew 25:36). Garry Wills, the Catholic historian and author, once said in answer to a question about the death penalty, “What do we know about Jesus and executions? He stopped one.” (John 8) We who call ourselves Christians, followers of Christ, know that we are as in need of mercy as the condemned man who hung next to Jesus on a cross (Luke 23: 39-43).

One of my favorite writers on this subject, Mark Osler, law professor at University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis and author of two books on the death penalty, Jesus on Death Row and Prosecuting Jesus, puts it clearly: God is God, and I am not.

Those truths have implications for us, as we stand in this moment where faith, law and policy in this country, and our beliefs about the sacredness of human life intersect.