Catholic Social Teaching

Our faith provides us with a guide for how to live as people of justice and mercy.

Learn about how Catholic Social Teaching Relates to:

Catholic Social Teaching & the Death Penalty

Rooted in both scripture and the rich tradition of our faith, Catholic Social Teaching is a guide for how to live as a people of justice and mercy. Catholic Social Teaching brings the teachings of Jesus and his call to discipleship to the larger societal conversation of social justice.

Catholic Social Teaching has 7 major themes:

Regarding the death penalty, the first and foremost aspect of the Church’s teaching is the belief in the inherent dignity of the human person as created in the image and likeness of God. Our Catechism states that this dignity “is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes.” As such, the death penalty is “inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” (Catholic Catechism 2267).

“Recourse to the death penalty on the part of legitimate authority, following a fair trial, was long considered an appropriate response to the gravity of certain crimes and an acceptable, albeit extreme, means of safeguarding the common good.

Today, however, there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes. In addition, a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state.

Lastly, more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection oaf citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.

Consequently, the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that ‘the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person,’ and she works with determination for its abolition worldwide.”

(Catholic Catechism 2267)

Life and Dignity of the Human Person

The human person, made in the image and likeness of God, is the foundation of a moral vision for society and stands at the heart of the Church’s understanding of justice.

“In our times a special obligation binds us to make ourselves the neighbor of every person without exception and of actively helping him [sic] when he comes across our path […] who disturbs our conscience by recalling the voice of the Lord, “As long as you did it for one of these the least of my brethren, you did it for me” (Matt. 25:40),” (Gaudium et spes 27).

The death penalty disregards this inherent dignity of the human person.

We are called to be a people of life.

As Catholics, we believe in a consistent ethic of life, from conception to natural death the sanctity of the human person cannot be diminished. “Where life is involved, the service of charity must be profoundly consistent. It cannot tolerate bias and discrimination, for human life is sacred and inviolable at every stage and in every situation; it is an indivisible good. We need then to show care for all life and for the life of everyone” (Evangelium vitae, 87). The death penalty violates this consistent ethic and does not conform to our pro-life teaching.

The death penalty threatens innocent life.

Despite our best efforts, our criminal justice system is not perfect. According to a 2014 study, at least 4% of those sentenced to death in the United States are innocent. The 161 people and counting who have been exonerated due to their innocence since 1973 exemplify that fact. For every 9 people who have been executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, one person has been exonerated after being proven innocent. The Catechism of the Catholic Church makes it clear: “The deliberate murder of an innocent person is gravely contrary to the dignity of the human being, to the golden rule, and to the holiness of the Creator,” (2261).

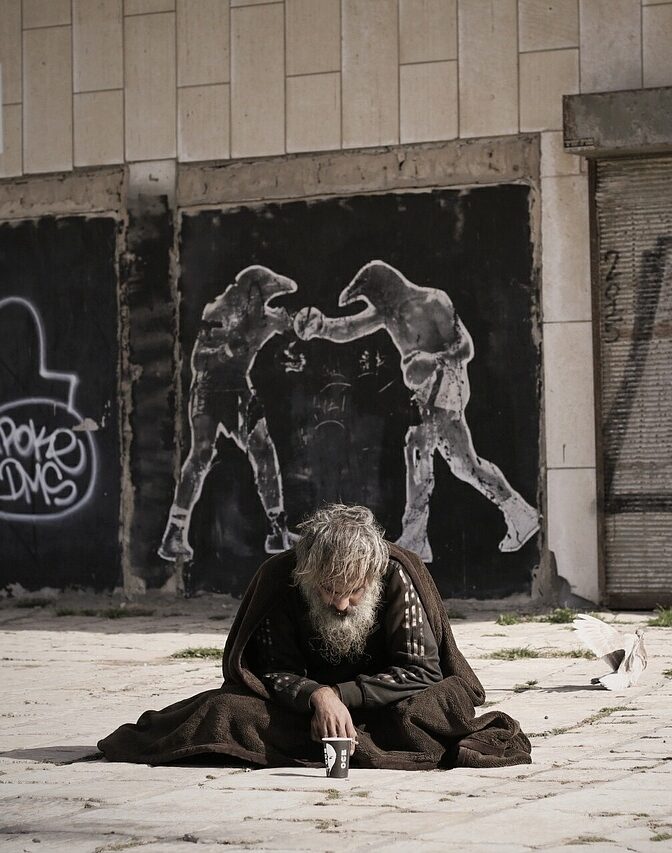

Preferential Option for the Poor and Vulnerable

Society is to be judged by how we care for the most vulnerable among us. While each human person has dignity and value, the marginalized among us demand special attention. For “whatever you do for the least of these sisters and brothers of mine, you did for me,” (Mt. 25: 40). When it comes to the death penalty, we must ask ourselves: who are we executing?

The death penalty disproportionately affects people of color.

More than half of the people on death row in this country are people of color. Black or Latino defendants are significantly more likely to get the death penalty than their white counterparts. Additionally, the race of the victim of a crime often plays a role in the use of the death penalty. Nationally, almost half (47%) of all murder victims since the 1970s have been black. Yet, for cases ending in a death sentence, only 17% of murder victims have been black. Even more upsetting is the fact that at least 60% of the 161 exonerees are either black or Latino. (1)

The death penalty affects those living in poverty.

Almost all death row inmates were unable to afford their own attorney at trial. Court-appointed attorneys often lack the experience necessary for capital trials, are overworked, and underpaid. This often results in poorly handled cases where mitigating factors and tools such as DNA evidence, severe mental illness, or Intellectual Disability may not be brought up. (2)

Those with Intellectual Disability and Severe Mental Illness are some of the most vulnerable in society, and those most affected by the death penalty.

Not only must these individuals overcome societal barriers to daily living but are also much more likely to become victims of crime and at special risk for wrongful conviction. In 2002, death penalty for persons with Intellectual Disability was determined unconstitutional, yet those with severe mental illness can still be killed. Even individuals with serious intellectual disabilities are still sentenced to death and executed. In 2017 alone at least 20 of the 23 people executed (87%) had evidence of mental illness, intellectual disability, brain damage or severe trauma. (3)

Call to Family, Community, and Participation

We encounter God in our encounters with one another. How we organize our society — in economics and politics, in law and policy — directly affects human dignity and the capacity of individuals to grow in community. All people have a right and a duty to participate in society, and we are all responsible for working together as one for the common good and well-being of all, especially the poor and vulnerable. The death penalty sacrifices the good of the community to serve the needs of vengeance and retribution. It is our responsibility to create a society of justice and peace.

The death penalty does not make society safer.

Over 85% of the nation’s top criminologists believe the death penalty is not a deterrent. In fact, in many states where the death penalty has been abolished the murder rate has fallen significantly. Many law enforcement officials argue that the death penalty does not serve as a deterrence and only re-directs vital resources away from addressing the real cause of crime. (4)

The death penalty costs an exorbitant amount more than non-capital cases.

More than a dozen states have found that death penalty cases are up to 10 times more expensive than comparable non-death penalty cases. These taxpayer dollars could be spent attending to the needs of victims of crime and addressing issues as to why people commit crimes in the first place (5)

The death penalty is arbitrarily isolated to only a small geographic area.

Roughly two percent of this nation’s counties have produced both a majority of all executions imposed since 1976 (52 percent) and of prisoners awaiting execution on death row (56 percent). In 2017, four states (Texas (7), Arkansas (4), Florida (3), and Alabama (3)) carried out 74% of the 23 executions held that year. The determination of a death sentence can be as arbitrary as the county in which you commit a crime. The death penalty has been equated to a geographical lottery; and does not conform to the demands of a just and peaceful society. (6)

The death penalty is something we, as community members, must work to end.

The principle of subsidiarity reminds us that functions of government should be performed at the lowest level possible, as long as they can be performed adequately. Catholic social teaching calls us all to take active and responsible participation in the way our communities function. The laws, systems, and processes of government should reflect our call to live justly and uphold the dignity of all people. It is our responsibility to speak out for the inherent value of all life to our elected officials and demand an end to the death penalty, “The State and other agencies of public law must not extend their ownership beyond what is clearly required by considerations of the common good properly understood, and even then there must be safeguards,” (Mater et magistra, 117).

Solidarity

We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences, and are called to be our sisters’ and brothers’ keepers. This means that no matter what wrongs a person may commit or what experiences their lives bring, we are called to live in a pursuit of justice and peace. “To love someone is to desire that person’s good and to take effective steps to secure it,” (Caritas in veritate, 7). The death penalty denies our call to solidarity by ignoring the pain and harm caused by violence.

The death penalty does not bring healing to victim’s families.

The necessarily long, complex death penalty trial process can force these families to re-live their trauma and pain. This costly process diverts money and resources from needed services for victims’ families. For many victims families the loss of another life is not the answer: “Pursuing the death penalty would not be the way we would want to honor our daughter’s life, nor would that decision have helped us deal with the painful reminders of her unfulfilled hopes and dreams,” (Vicki Schieber, CMN Speaker). As Catholics, we are called to care for these victims families, to bear witness to their experiences, and allow them to heal from the harm they have experienced, not create more victim’s family members with the death penalty.

The use of the death penalty denies our call to care for the least of these.

The death penalty unjustly targets people of color, those with intellectual disability and mental illness; it affects those living in poverty and risks killing innocent life. Our call to solidarity is our call to live out a preferential option for the poor and vulnerable. The death penalty stands in direct contradiction to this call to solidarity: “whatever you do for the least of these sisters and brothers of mine, you did for me,” (Mt. 25: 40).

Sources:

(1) Death Penalty Information Center, Equal Justice USA, Equal Justice Initiative

(2) Death Penalty Information Center, Equal Justice USA

(3) Death Penalty Information Center

(4) Equal Justice USA

(5) Death Penalty Information Center

(6) Death Penalty Information Center

Catholic Social Teaching & Restorative Justice

Written by Susan Sharpe, Ph.D. and adapted for Catholic Mobilizing Network

Rooted in both scripture and the rich tradition of our faith, Catholic Social Teaching is a guide for how to live as a people of justice and mercy. Catholic Social Teaching brings the teachings of Jesus and his call to discipleship to the larger societal conversation of social justice.

Catholic Social Teaching has 7 major themes:

The U.S. Legal System Asks:

What law was broken?

Who is guilty?

How should they be punished?

Restorative Justice Asks:

What was the harm?

Who has been harmed?

What are the needs?

Whose obligations are these?

What should be done to put things right?

All of these principles are evident in restorative justice, “an approach to achieving justice that involves, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense or harm to collectively identify and address harms, needs, and obligations in order to heal and put things as right as possible.”(2)

In addition to repairing the harm done by wrongful behavior, restorative justice also fosters skills and attitudes that make injustice less likely to occur and easier to repair when it does.

Life and Dignity of the Human Person

Every person is created in the image and likeness of God, and therefore has inalienable dignity — no matter the harm one has caused or suffered.

The first question that restorative justice asks is “what was the harm?” In other words, whose dignity was violated and how?

Restorative justice upholds that the dignity and needs of each person must be at the center of a response to harm, no matter their role, because no person is disposable.

If there were oppressive systems or conditions that contributed to the harm, the common good demands addressing those injustices as well.

Option for the Poor and Vulnerable

The option for/with poor and vulnerable people calls us to prioritize those who are marginalized by violence, crime, incarceration, and systemic oppression.

By asking the question “who has been harmed?” restorative justice puts the experiences and voices of those most impacted at the center of the process.

When crime has occurred, this means giving the victim(s) meaningful voice in the outcome and calling upon the person(s) who caused harm to make amends for the damage they caused.

In the spirit of subsidiarity, restorative practices create opportunities for those closest to the situation to participate in the decisions that will affect them.

Solidarity

We are one human family and are called to be our sisters’ and brothers’ keepers. Because we are deeply interconnected in a web of relationships, harm has rippling effects.

Restorative justice sees people neither as victims in need of pity nor offenders deserving of punishment, but rather as people whose lives have intersected through harmful behavior and whose needs (physical, material, emotional, and spiritual) must be met.

This is why family members, support people, and community members are invited to be part of restorative dialogues.

Beyond particular instances of harm, practices like circle process create opportunities to slow down, share deeply, and hear one another’s stories, honoring our common dignity

Call to Family, Community, and Participation

We encounter God in our interactions with one another. Each person has a right and a duty to participate in society and holds a responsibility to work with others for the common good and well-being of all — especially the poor and vulnerable.

Restorative justice invites people to share their stories in their own terms and to hear others’ stories with respect, together seeking a shared narrative of what happened, why, and how best to move forward.

Incarceration removes a person from society. Often, victimization can have a similar effect. A restorative approach seeks ways to limit isolation and find healing in communion with one another.

Rights and Responsibilities

Like Catholic Social Teaching, restorative justice recognizes that rights and responsibilities are interwoven and asks, “whose obligations are these?”

We all have basic rights to life and decency; living justly in community requires being accountable for how our choices and actions affect other people.

From this perspective, accountability can take many different forms: taking responsibility, asking for forgiveness, returning or replacing material items, making a commitment to changing behavior, etc.

In a restorative process, ways of making amends can be mutually determined by those involved, rather than solely imposed by the criminal legal system.

Help CMN end the death penalty, advance justice, and begin healing

Join our community today.